Just Before Paradise

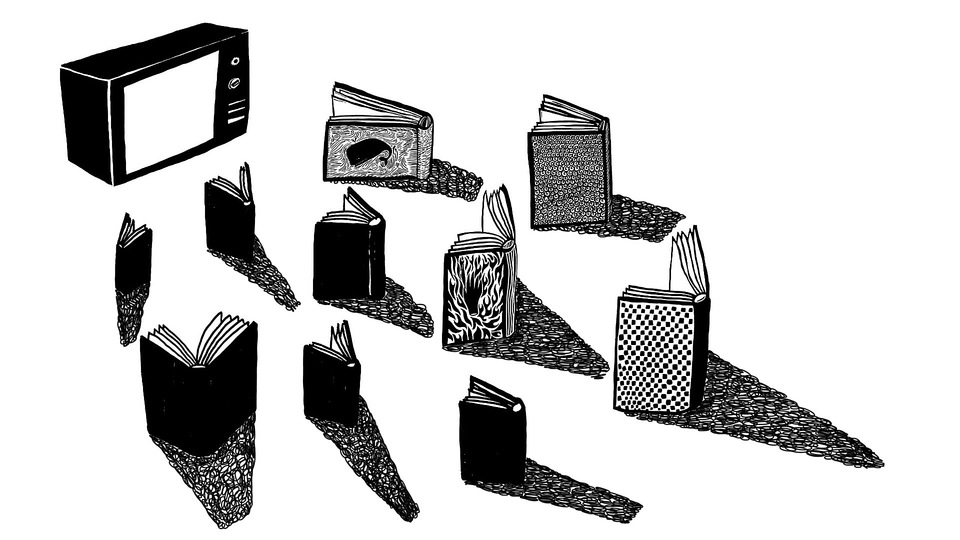

“And just as we learn about our lives from others, so, too, do we let others shape our understanding of the city in which we live,” says Orhan Pamuk in his memoirs, where the leading role is played by the city that embodies the Orientalist visions of the West more than any other.

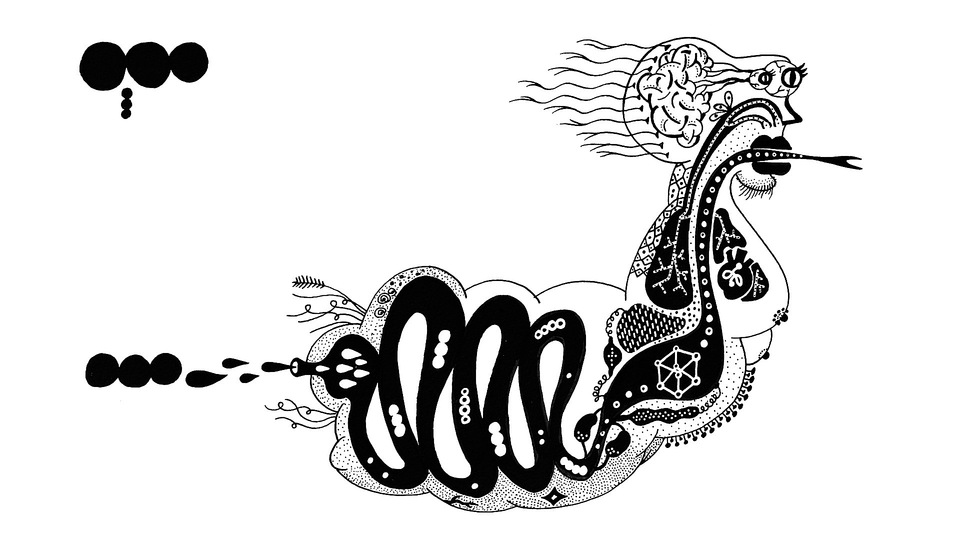

Turkey, as it has always been in its history, and never so much so as in these past few decades, has once again become the vanishing point of world geopolitics. Istanbul’s unique and ever-changing tension is the epicenter of an earthquake that is shaking the very foundations of modernity; the city is rediscovering its vocation as a barometer for the balance between East and West, North and South. As it struggles to strike a balance between a European vocation and a political belonging that is yet to be accomplished, Istanbul is once again, and in a wholly new way, the theater of a conflict that has never died out between twentieth-century secularism and the public reaffirmation of religions, between freedom of expression and the jealous safeguarding of identities...

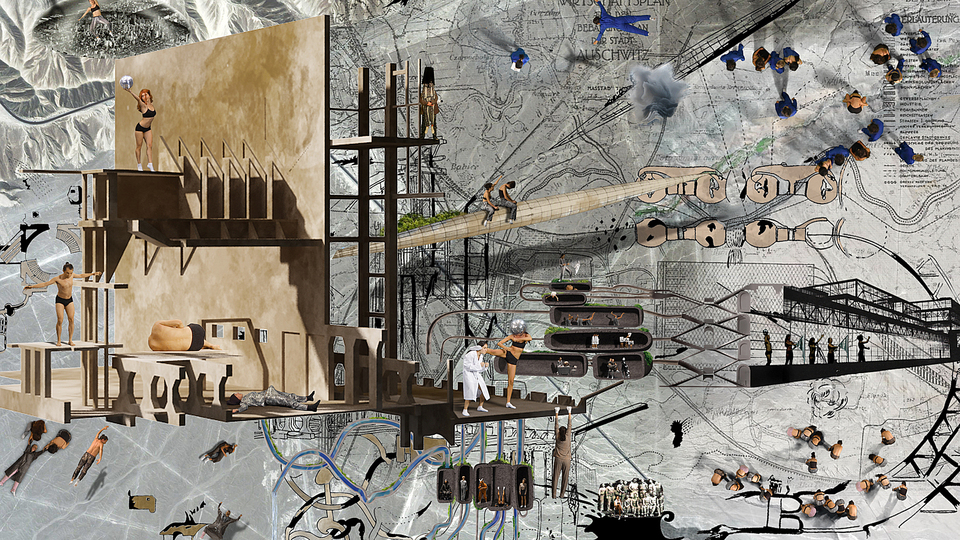

Istanbul’s contradictory model of urban development represents in the most intensive way the profound contradiction and conflicts of Turkish society today. Modernization, with urbanization as its avant-garde, has been the main project for the building of the new nation-state as a Republic raised from the ruin of the Ottoman Empire nearly a century ago. An entirely new capital, modeled on European capital cities, was designed and built in the founding years of the Republic. It took a radical westernization program to turn the Turkish society into a modern one. However, “Turkish modernity” has always been a changing concept in permanent negotiations with different historical momentums, and the outcomes permanently swing between opposing and belligerent ideologies and socio-cultural models: “West” vs. “East,” modern vs. tradition, the national vs. the imperial, secularism vs. religion (Islam and others), and the local vs. the global, etc. They have always ended up becoming new hybrids, insolvably contradictory and even incongruous. But they are definitely energetic and infinitely expansive. The city of Istanbul, after a few decades of shrinking due to its status as the former capital of the Empire, has been brought back to the central stage of the national economic and social development since the 1950s. It has once again become the hub of the country’s economic and cultural activities. Modernization of the Turkish industry introduced new programs of urban expansion. Millions of migrant workers from other parts of the country rushed into the city and settled in illegally occupied areas. They built shelters overnight with whatever affordable materials they could find. Slums, then, mushroomed all around to form major parts of the city. Along with new industrial, commercial and government buildings and avenues, they have transformed the city into a unique scenery, mixing the historical and the contemporary in the most unlikely but vivid way. This has given Istanbul a new attraction: the coexistence of the formal and the informal, the rich and the poor, the new and the old, derived from multicultural-ethnic-religious roots, has made the city one of the most beautiful, monumental but enigmatic metropolises on earth.

For the last decade, one can observe that the rise of new economic and geopolitical tensions is exerting a great influence on the city’s evolution: in the name of integration in the global market and economic growth, the authorities encourage and organize major transformations of the city. The city of the secular Republican modernity and industrialization is rapidly transformed into a postmodern city of neoliberal capitalism – driven by the privatization of public services, finance, real estates, tourism, consumerism and the rise of “creative industry.” It has become a new and infinite playground for global capital. Accordingly, a typical typology of “global urbanism” has been planned and developed upon the multiple strata of the historic city to facilitate consumer life and global mobility: the new program of urban developments is focusing on shopping malls, high-end residences, entertainment, airports and bridges, etc.

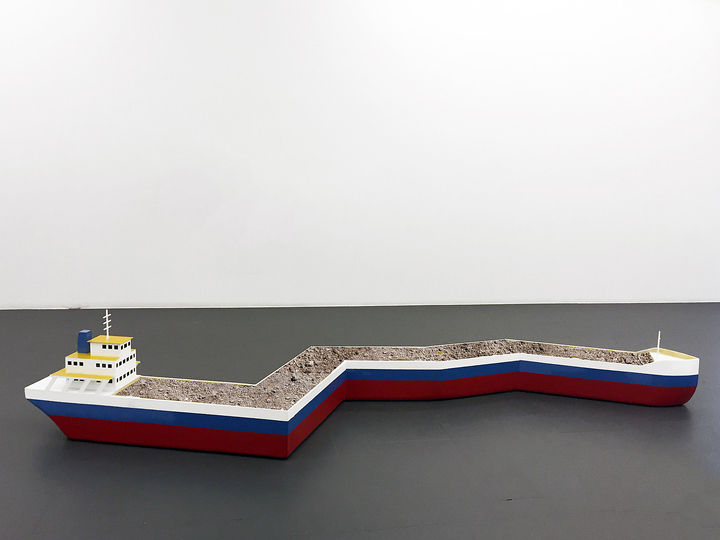

To meet the needs of the emerging “middle class,” the government has pushed for immense programs of high-rise housing and upper-scale residences along with new business districts with office towers. This has been promoted by the official agency TOKI in close collaboration with private developers. The outcome is a new skyline for Istanbul that rockets into the sky. But the price to pay is massive gentrification, sending the poor population out of their slums and expelling them from the city center. There are more ambitious projects to expand the urban space into the hinterland with unexplored forest and natural resources. The project for a large canal and airport will soon be followed by the destruction of the natural environment. The city’s ecological sustainability is under threat.

This process is not really new. By tracing back to the several moments in Istanbul’s urban development, one can easily see there has always been a close relationship between the country’s political changes and the urban transformation. During the first period of the Republic, Istanbul was disfavored and shrinking. Then, in the 1950s, with the victory of the Democratic Party, Istanbul was brought back to the center of Turkish modernization with ambitious, modernist-oriented, pro-American, urban expansion and new constructions. The periods of “coup d’état” (1960s, 1980s) had also seen other waves of urban development. A process of integration in the system of global capitalist economy was launched and unfolding. With the takeover of the AKP, the Islamist Justice and Development Party in the last decade, this process has been particularly accelerated and expanded.

In the meantime, the urban expansion program is also designed to become a conveyer of the neo- conservatism of social values reflecting political Islam’s agenda and the conservative ideology of the capital power. The new buildings promoted by the government and developers tend to adopt a pastiche style, combining eccentric postmodern “high-tech” looks with motifs of reinvented “tradition” and neo-Ottoman “memory.” This is imposing a new container for the secularist modernism created in the previous decades. Moreover, some symbolic gestures have been made to build a greater number of mosques and other buildings with Islamic imageries. Currently, the Çamlıca Camii Külliyesi (Çamlıca Mosque Complex), Turkey’s largest mosque, is being built on the Asian side overlooking the Bosphorus Strait.

This seems to introduce a model of “good life” for the population. In truth, this rather tends to camouflage the contradictions and violence exerted upon normal citizens, namely the majority who suffer from this mutation owing to the loss of their households, cultural roots, and freedom. Social division and replacement of the secular values symbolized by urban environment and architecture have provoked widespread protest and resistance. The events that took place in Gezi Park and Taksim Square in 2013, involving occupation by the citizens, especially young activists and artists, was the ultimate outcry of this resistance movement.

ISTANBUL. PASSION, JOY, FURY was on show in 2016 at MAXXI Rome.

Turkey, as it has always been in its history, and never so much so as in these past few decades, has once again become the vanishing point of world geopolitics. Istanbul’s unique and ever-changing tension is the epicenter of an earthquake that is shaking the very foundations of modernity; the city is rediscovering its vocation as a barometer for the balance between East and West, North and South. As it struggles to strike a balance between a European vocation and a political belonging that is yet to be accomplished, Istanbul is once again, and in a wholly new way, the theater of a conflict that has never died out between twentieth-century secularism and the public reaffirmation of religions, between freedom of expression and the jealous safeguarding of identities...

Istanbul’s contradictory model of urban development represents in the most intensive way the profound contradiction and conflicts of Turkish society today. Modernization, with urbanization as its avant-garde, has been the main project for the building of the new nation-state as a Republic raised from the ruin of the Ottoman Empire nearly a century ago. An entirely new capital, modeled on European capital cities, was designed and built in the founding years of the Republic. It took a radical westernization program to turn the Turkish society into a modern one. However, “Turkish modernity” has always been a changing concept in permanent negotiations with different historical momentums, and the outcomes permanently swing between opposing and belligerent ideologies and socio-cultural models: “West” vs. “East,” modern vs. tradition, the national vs. the imperial, secularism vs. religion (Islam and others), and the local vs. the global, etc. They have always ended up becoming new hybrids, insolvably contradictory and even incongruous. But they are definitely energetic and infinitely expansive. The city of Istanbul, after a few decades of shrinking due to its status as the former capital of the Empire, has been brought back to the central stage of the national economic and social development since the 1950s. It has once again become the hub of the country’s economic and cultural activities. Modernization of the Turkish industry introduced new programs of urban expansion. Millions of migrant workers from other parts of the country rushed into the city and settled in illegally occupied areas. They built shelters overnight with whatever affordable materials they could find. Slums, then, mushroomed all around to form major parts of the city. Along with new industrial, commercial and government buildings and avenues, they have transformed the city into a unique scenery, mixing the historical and the contemporary in the most unlikely but vivid way. This has given Istanbul a new attraction: the coexistence of the formal and the informal, the rich and the poor, the new and the old, derived from multicultural-ethnic-religious roots, has made the city one of the most beautiful, monumental but enigmatic metropolises on earth.

For the last decade, one can observe that the rise of new economic and geopolitical tensions is exerting a great influence on the city’s evolution: in the name of integration in the global market and economic growth, the authorities encourage and organize major transformations of the city. The city of the secular Republican modernity and industrialization is rapidly transformed into a postmodern city of neoliberal capitalism – driven by the privatization of public services, finance, real estates, tourism, consumerism and the rise of “creative industry.” It has become a new and infinite playground for global capital. Accordingly, a typical typology of “global urbanism” has been planned and developed upon the multiple strata of the historic city to facilitate consumer life and global mobility: the new program of urban developments is focusing on shopping malls, high-end residences, entertainment, airports and bridges, etc.

To meet the needs of the emerging “middle class,” the government has pushed for immense programs of high-rise housing and upper-scale residences along with new business districts with office towers. This has been promoted by the official agency TOKI in close collaboration with private developers. The outcome is a new skyline for Istanbul that rockets into the sky. But the price to pay is massive gentrification, sending the poor population out of their slums and expelling them from the city center. There are more ambitious projects to expand the urban space into the hinterland with unexplored forest and natural resources. The project for a large canal and airport will soon be followed by the destruction of the natural environment. The city’s ecological sustainability is under threat.

This process is not really new. By tracing back to the several moments in Istanbul’s urban development, one can easily see there has always been a close relationship between the country’s political changes and the urban transformation. During the first period of the Republic, Istanbul was disfavored and shrinking. Then, in the 1950s, with the victory of the Democratic Party, Istanbul was brought back to the center of Turkish modernization with ambitious, modernist-oriented, pro-American, urban expansion and new constructions. The periods of “coup d’état” (1960s, 1980s) had also seen other waves of urban development. A process of integration in the system of global capitalist economy was launched and unfolding. With the takeover of the AKP, the Islamist Justice and Development Party in the last decade, this process has been particularly accelerated and expanded.

In the meantime, the urban expansion program is also designed to become a conveyer of the neo- conservatism of social values reflecting political Islam’s agenda and the conservative ideology of the capital power. The new buildings promoted by the government and developers tend to adopt a pastiche style, combining eccentric postmodern “high-tech” looks with motifs of reinvented “tradition” and neo-Ottoman “memory.” This is imposing a new container for the secularist modernism created in the previous decades. Moreover, some symbolic gestures have been made to build a greater number of mosques and other buildings with Islamic imageries. Currently, the Çamlıca Camii Külliyesi (Çamlıca Mosque Complex), Turkey’s largest mosque, is being built on the Asian side overlooking the Bosphorus Strait.

This seems to introduce a model of “good life” for the population. In truth, this rather tends to camouflage the contradictions and violence exerted upon normal citizens, namely the majority who suffer from this mutation owing to the loss of their households, cultural roots, and freedom. Social division and replacement of the secular values symbolized by urban environment and architecture have provoked widespread protest and resistance. The events that took place in Gezi Park and Taksim Square in 2013, involving occupation by the citizens, especially young activists and artists, was the ultimate outcry of this resistance movement.

ISTANBUL. PASSION, JOY, FURY was on show in 2016 at MAXXI Rome.

Magazines