Modigliani: Your real duty is to save your dream

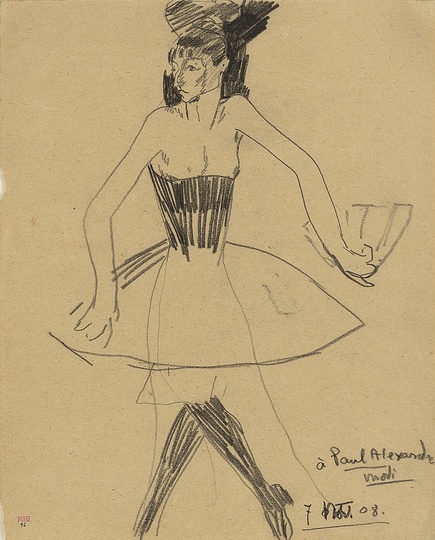

"What I am searching for is neither the real nor the unreal, but the subconscious, the mystery of what is instinctive in the human race." - Written in a sketchbook by Modigliani in 1907.

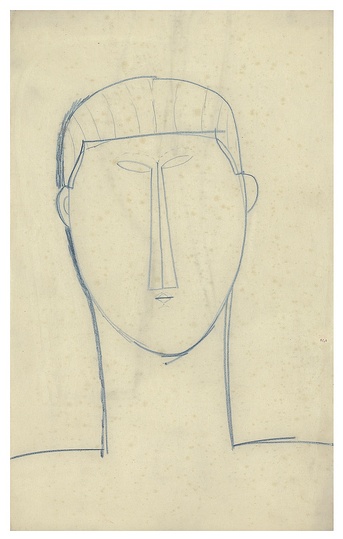

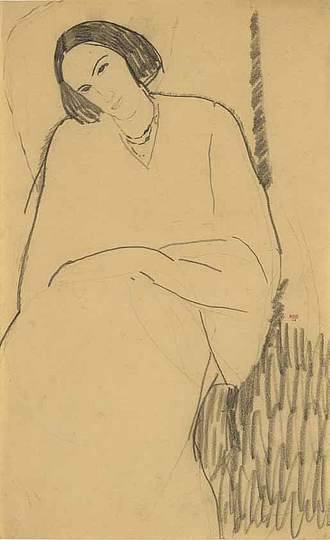

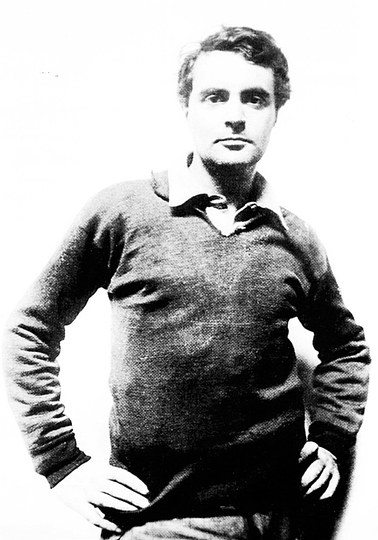

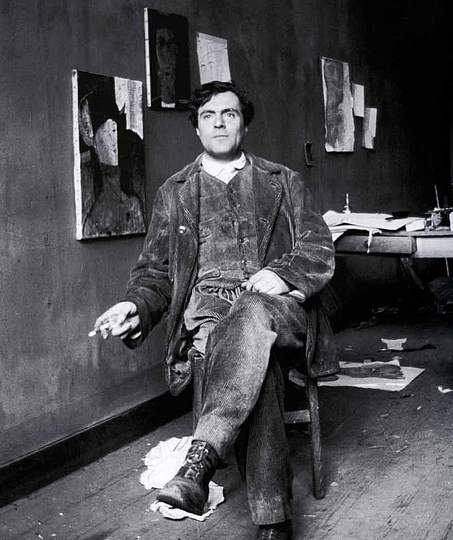

For Modigliani, ‘Beauty’, ‘Life’ and ‘Art’ were a sacred, single entity. ‘Beauty’ was at the core of his creative being. The human face and form have, for thousands of years, been the artist’s principal subject. Yet Modigliani depicted both in a way that became, and will remain, entirely his own. Modigliani was a delicate child, and at the age of eleven became ill with pleurisy, the first of three serious childhood illnesses. At sixteen he almost died of tuberculosis. He sensed his life would be brief and that his mission was to create, for the benefit of others, his own vision of beauty and veneration for life. Some months later, in 1901, he wrote from Rome to his artist friend Oscar Ghiglia: "I myself am the plaything of very powerful energies which are born and die. I would like instead that my life is like a very rich river which flows with joy upon the earth. …I am trying to formulate with the greatest lucidity the truths of art and life I have discerned scattered amongst the beauties of Rome; and as their inner meaning becomes clear to me, I shall seek to reveal and to re-arrange their composition, I could almost say metaphysical architecture, in order to create out of it my truth of life, beauty and art."

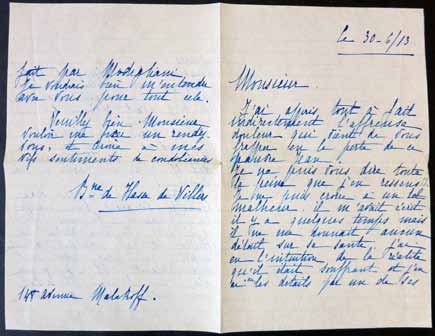

That Modigliani should, at so young an age, be concerned with extracting from the ruins of ancient Rome timeless truths, in order to ‘rearrange’ them into his own vision of ‘life, beauty and art’, makes this a particularly remarkable visionary statement of intent. And to Ghiglia later that year: "We others (excuse the plural) have different rights from normal people, for we have different needs which place us above – this must be said and believed – their morality. It is our duty never to be consumed by the sacrificial fire. Your real duty is to save your dream. Beauty too has some painful duties: these produce, however, the noblest achievements of the soul."

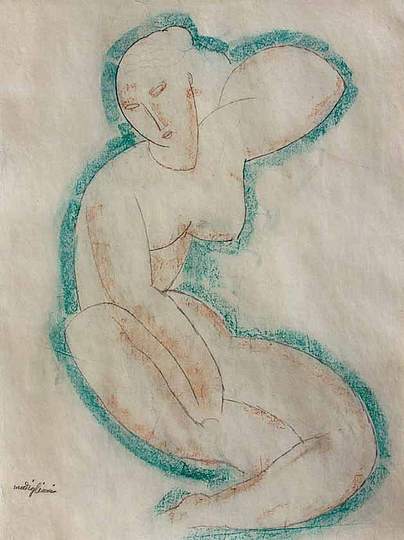

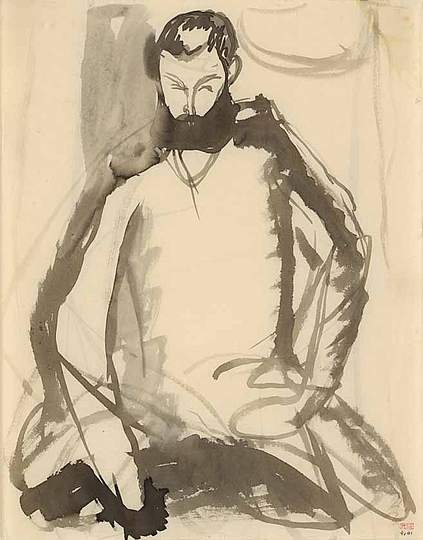

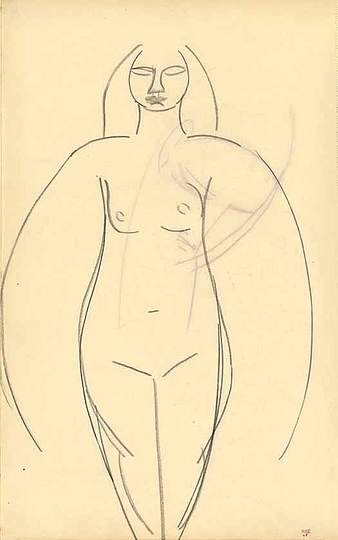

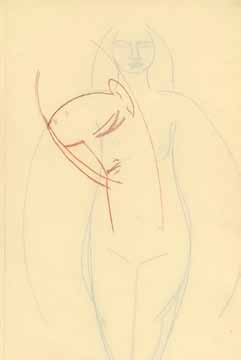

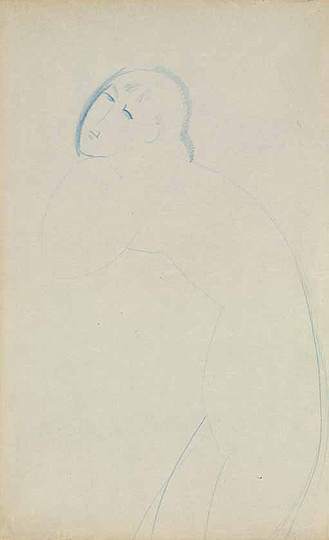

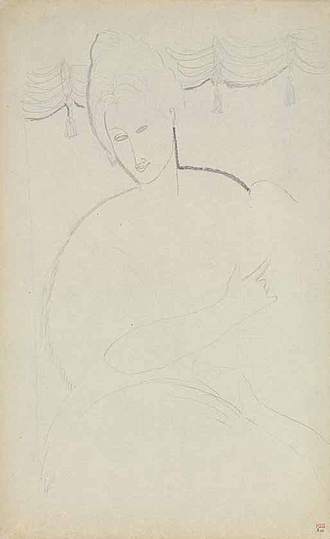

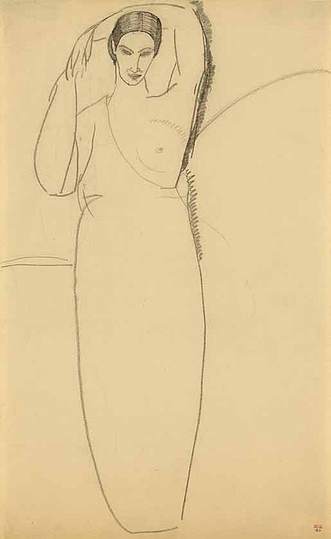

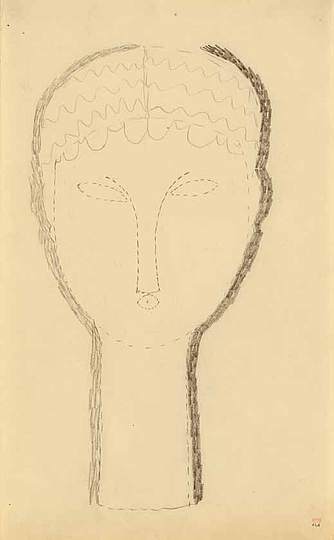

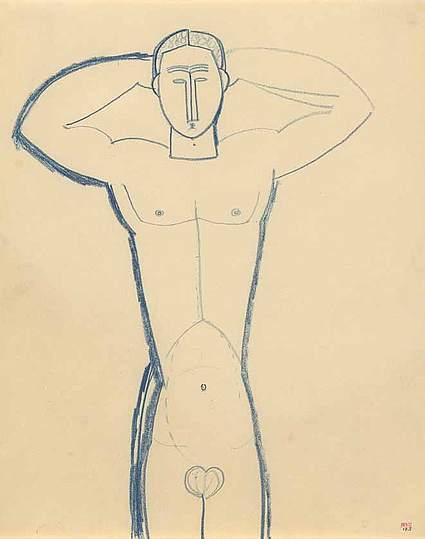

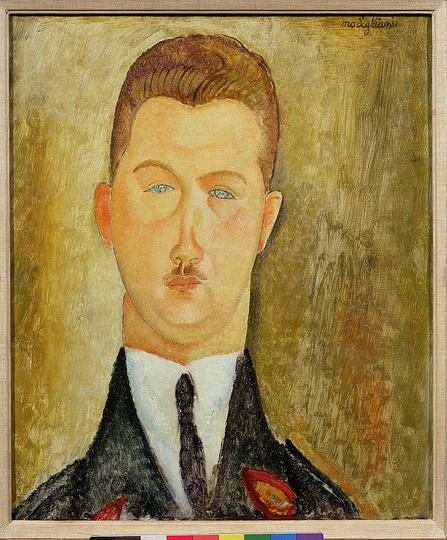

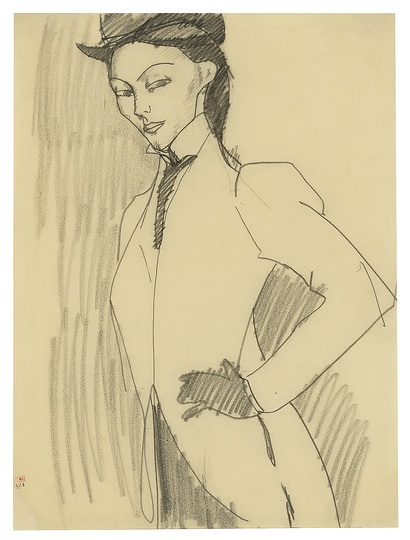

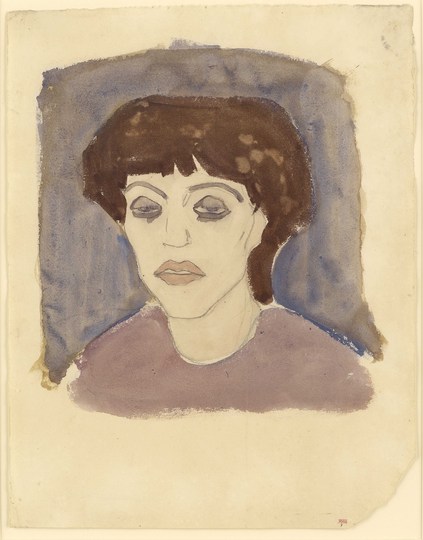

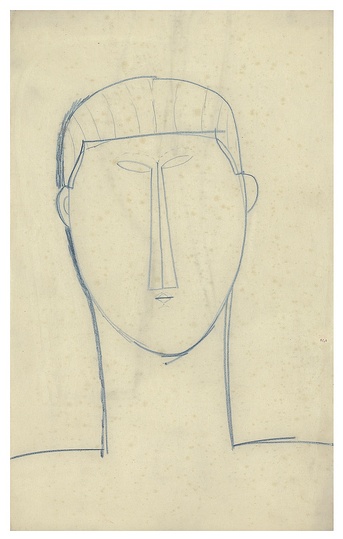

The passion and clarity with which Modigliani was already able to express such deeply held beliefs reveal his originality; his uncompromising determination to create his own visual aesthetic ideal. And his absolute conviction that he would succeed. His arrival in Paris in the winter of 1906 accelerated this aesthetic, spiritual alchemy as he absorbed into the prism of his extreme sensibility art forms encompassing some four thousand years, among them the art of the Cyclades, ancient Egypt, Greece, the Etruscans, Rome, Asia, Africa and his beloved Italy. But why did each of these seemingly disparate cultures and art forms speak so directly to Modigliani? Where, for him, lay their unifying energy and individual inspiration? And what collective insight do they reveal into his art? The symbolic simplicity of the Cycladic figure and face. The mesmerising aura, from the grave, of Egyptian goddesses and queens. The purity and majesty of Greek sculpture. The gentle humour of Etruscan art. The noble austerity of Roman art. The sensual movement of female Indian dancers. The serenity of Buddhist art. The raw energy of the African artist’s gouged-out portrayal of the human soul. And Modigliani’s deep feeling for his Italian artist ancestors, among them Giotto, Simone Martini, Michelangelo, Botticelli and Titian – with their tender spirituality, humanity and adoration of the human form From each, he took those elements which accorded with his own character and spiritual aesthetic, so that they became naturally and mysteriously fused with his highly personal artistic vision. He was not interested in fleeting stylistic fads for he considered himself part of a timeless, essentially unchanging artistic-spiritual tradition expressing an enduring, inspiring human response to the beauty and mystery of life.

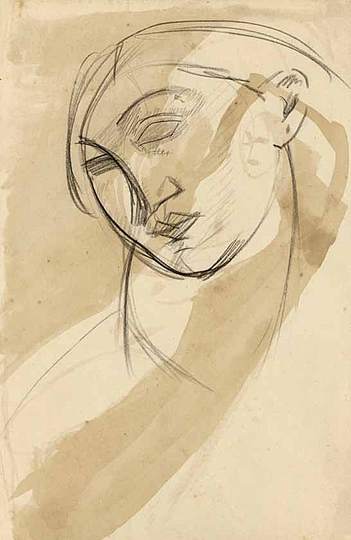

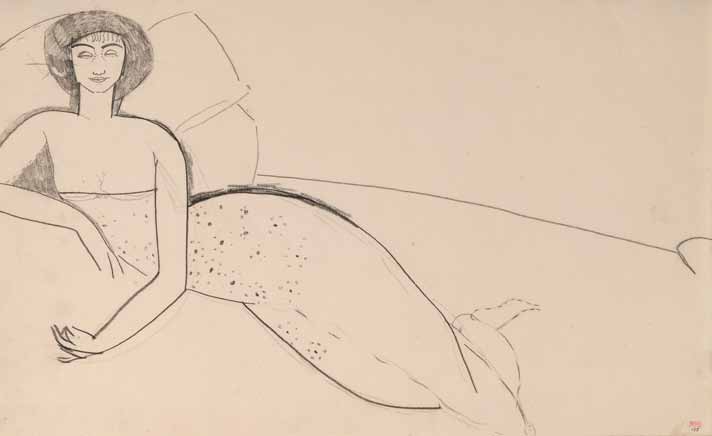

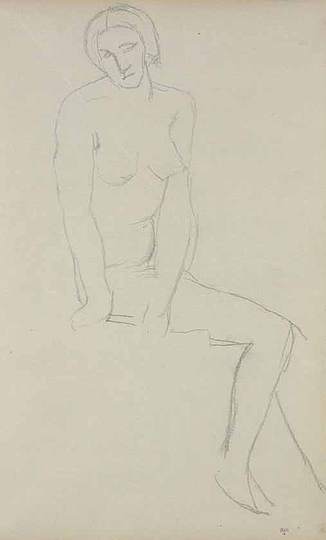

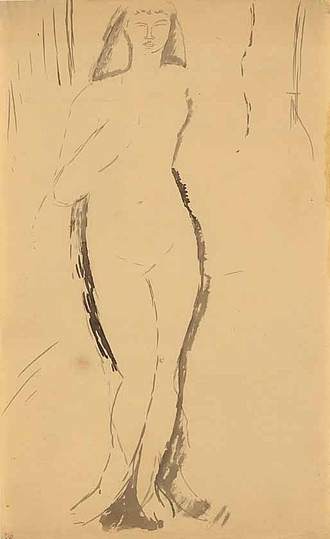

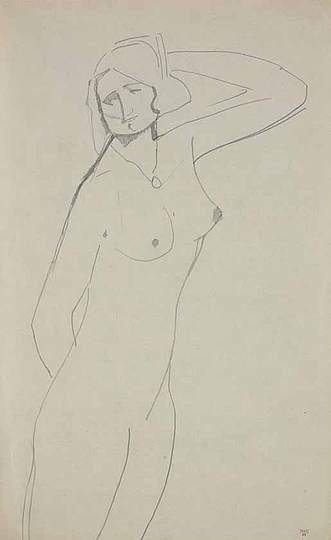

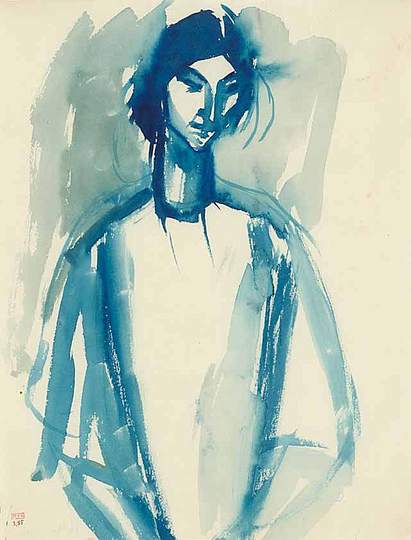

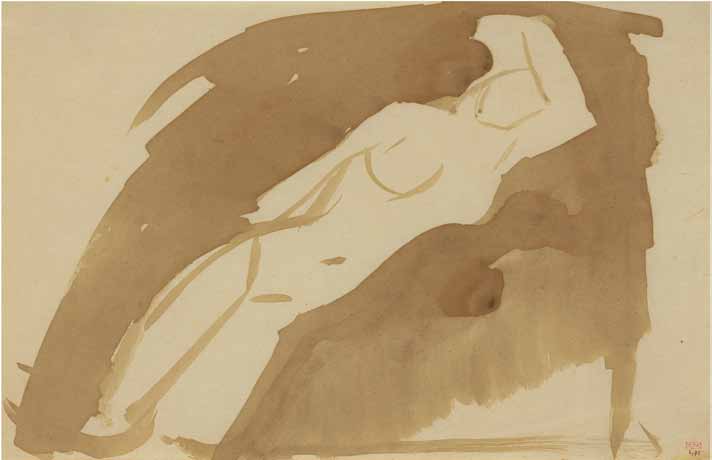

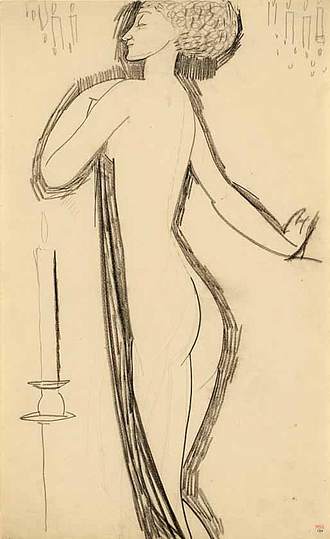

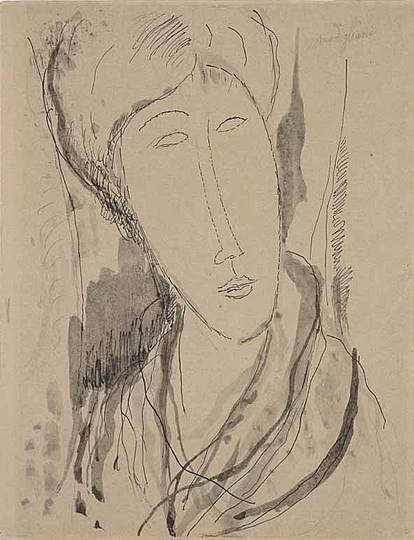

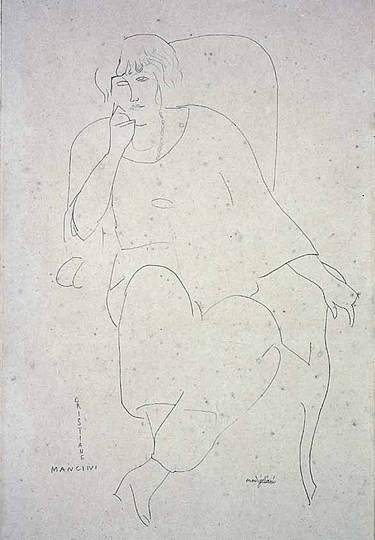

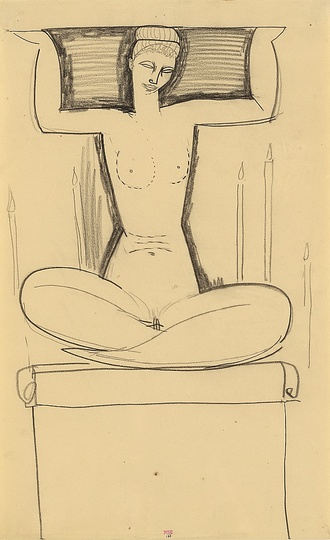

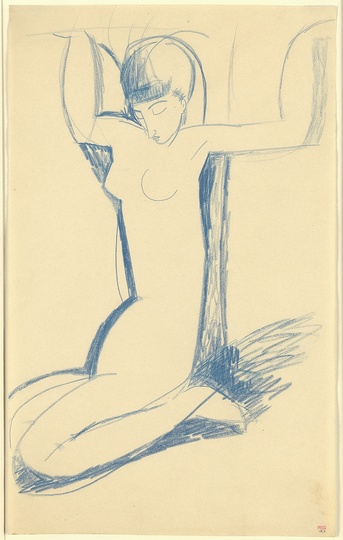

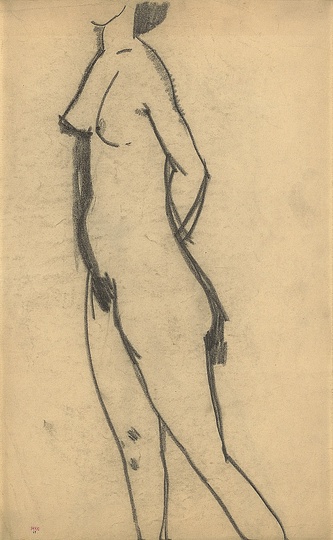

Modigliani’s meeting, in 1910, with Anna Akhmatova coincided, at a critical juncture in his art, with his need to portray the ‘neither real nor unreal angel spirits’ he dreamt of. Sculpture became his principal focus of expression – a vital, cathartic rite of passage for which he chose the elemental, neutrally coloured substance of stone. Through his carvings and related drawings he forged his vision of humanity. Yet whilst many of his faces and figures are anonymous and often androgynous, certain sculptures and drawings directly mirror the appearance and spirit of Anna Akhmatova whose charismatically beautiful, elongated face and body influenced the course of his art. It is often claimed that Modigliani wanted to devote himself to carving in stone and only his delicate health prevented this. However sculpture alone would never have provided complete fulfilment for an artist so in love with drawing and painting, and so able, through them, to convey the subtlest nuance of character, mood and form. Also an artist utterly entranced and captivated by his fellow beings; and intent upon portraying their inner beauty and richness of character. "To do any work, I must have a living person. I must be able to see him opposite me…" Modigliani told the painter Leopold Survage. Modigliani believed, like Keats, that ‘Beauty’ is ‘Truth’, and could save the world. These drawings mirror the mysterious forces acting within and through him, their harmonious, vibrant lines forming visual sounds of sublime, enduring beauty emanating from a place beyond our comprehension. Lunia Czechowska, who sat for one of Modigliani’s last portraits, recounts a moving incident, not long before he died. ‘While I was preparing dinner, he asked me to lift my head for a few moments and by the light of a candle, he drew a beautiful sketch on which he wrote:’ Life is a gift: from the few to the many: from those who know and who have to those who do not know and do not have.

© Estorick Foundation, London.

For Modigliani, ‘Beauty’, ‘Life’ and ‘Art’ were a sacred, single entity. ‘Beauty’ was at the core of his creative being. The human face and form have, for thousands of years, been the artist’s principal subject. Yet Modigliani depicted both in a way that became, and will remain, entirely his own. Modigliani was a delicate child, and at the age of eleven became ill with pleurisy, the first of three serious childhood illnesses. At sixteen he almost died of tuberculosis. He sensed his life would be brief and that his mission was to create, for the benefit of others, his own vision of beauty and veneration for life. Some months later, in 1901, he wrote from Rome to his artist friend Oscar Ghiglia: "I myself am the plaything of very powerful energies which are born and die. I would like instead that my life is like a very rich river which flows with joy upon the earth. …I am trying to formulate with the greatest lucidity the truths of art and life I have discerned scattered amongst the beauties of Rome; and as their inner meaning becomes clear to me, I shall seek to reveal and to re-arrange their composition, I could almost say metaphysical architecture, in order to create out of it my truth of life, beauty and art."

That Modigliani should, at so young an age, be concerned with extracting from the ruins of ancient Rome timeless truths, in order to ‘rearrange’ them into his own vision of ‘life, beauty and art’, makes this a particularly remarkable visionary statement of intent. And to Ghiglia later that year: "We others (excuse the plural) have different rights from normal people, for we have different needs which place us above – this must be said and believed – their morality. It is our duty never to be consumed by the sacrificial fire. Your real duty is to save your dream. Beauty too has some painful duties: these produce, however, the noblest achievements of the soul."

The passion and clarity with which Modigliani was already able to express such deeply held beliefs reveal his originality; his uncompromising determination to create his own visual aesthetic ideal. And his absolute conviction that he would succeed. His arrival in Paris in the winter of 1906 accelerated this aesthetic, spiritual alchemy as he absorbed into the prism of his extreme sensibility art forms encompassing some four thousand years, among them the art of the Cyclades, ancient Egypt, Greece, the Etruscans, Rome, Asia, Africa and his beloved Italy. But why did each of these seemingly disparate cultures and art forms speak so directly to Modigliani? Where, for him, lay their unifying energy and individual inspiration? And what collective insight do they reveal into his art? The symbolic simplicity of the Cycladic figure and face. The mesmerising aura, from the grave, of Egyptian goddesses and queens. The purity and majesty of Greek sculpture. The gentle humour of Etruscan art. The noble austerity of Roman art. The sensual movement of female Indian dancers. The serenity of Buddhist art. The raw energy of the African artist’s gouged-out portrayal of the human soul. And Modigliani’s deep feeling for his Italian artist ancestors, among them Giotto, Simone Martini, Michelangelo, Botticelli and Titian – with their tender spirituality, humanity and adoration of the human form From each, he took those elements which accorded with his own character and spiritual aesthetic, so that they became naturally and mysteriously fused with his highly personal artistic vision. He was not interested in fleeting stylistic fads for he considered himself part of a timeless, essentially unchanging artistic-spiritual tradition expressing an enduring, inspiring human response to the beauty and mystery of life.

Modigliani’s meeting, in 1910, with Anna Akhmatova coincided, at a critical juncture in his art, with his need to portray the ‘neither real nor unreal angel spirits’ he dreamt of. Sculpture became his principal focus of expression – a vital, cathartic rite of passage for which he chose the elemental, neutrally coloured substance of stone. Through his carvings and related drawings he forged his vision of humanity. Yet whilst many of his faces and figures are anonymous and often androgynous, certain sculptures and drawings directly mirror the appearance and spirit of Anna Akhmatova whose charismatically beautiful, elongated face and body influenced the course of his art. It is often claimed that Modigliani wanted to devote himself to carving in stone and only his delicate health prevented this. However sculpture alone would never have provided complete fulfilment for an artist so in love with drawing and painting, and so able, through them, to convey the subtlest nuance of character, mood and form. Also an artist utterly entranced and captivated by his fellow beings; and intent upon portraying their inner beauty and richness of character. "To do any work, I must have a living person. I must be able to see him opposite me…" Modigliani told the painter Leopold Survage. Modigliani believed, like Keats, that ‘Beauty’ is ‘Truth’, and could save the world. These drawings mirror the mysterious forces acting within and through him, their harmonious, vibrant lines forming visual sounds of sublime, enduring beauty emanating from a place beyond our comprehension. Lunia Czechowska, who sat for one of Modigliani’s last portraits, recounts a moving incident, not long before he died. ‘While I was preparing dinner, he asked me to lift my head for a few moments and by the light of a candle, he drew a beautiful sketch on which he wrote:’ Life is a gift: from the few to the many: from those who know and who have to those who do not know and do not have.

© Estorick Foundation, London.

Magazines